I promised I’d dig a bit deeper into the book data, so here goes!

We have seven academic schools in the university, so I thought it would be interesting to see how the range of titles broke down by each school. As previously noted, the borrowing patterns seem to have changed at the end of 2005/start of 2006, so here’s the percentage change for the two periods…

academic school average range of titles borrowed % change

2000-2005 2006-2008

Music, Humanities & Media 16,760 20,468 122.1%

Business 9,431 11,402 120.9%

Computing & Engineering 7,033 6,771 96.3%

Education 12,485 11,909 95.4%

Human & Health Sciences 16,427 20,274 123.4%

Applied Sciences 7,356 7,562 102.8%

Art, Design & Architecture 9,361 12,309 131.4%

So, first of all, the increase in range of titles being borrowed isn’t across the board. I knew Computing & Engineering borrowing had been in decline for a number of years, but I’m surprised to see that the same applies for Education. Applied Sciences has stayed pretty much the same, but the other 4 schools have seen sizeable increases in the range of titles being borrowed.

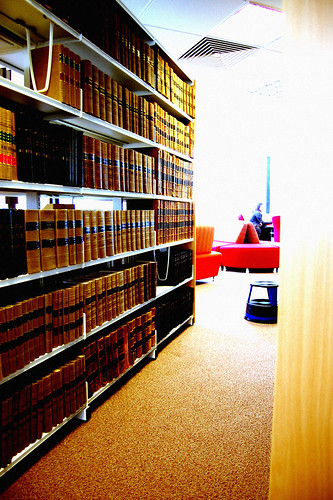

The Art & Design section of the library was revamped in 2005, so it could be that we’ve seen an increase in the number of students using the library and that has driven the increased borrowing since then for that school.

A few of the comments suggested that loans per borrower would be a useful metric. Unfortunately I don’t have the data for the total number of students in each school per year, so I’m using the total number of active borrowers instead…

academic school average loans per active borrower % change

2000-2005 2006-2008

Music, Humanities & Media 26.1 25.7 98.6%

Business 10.2 12.3 121.4%

Computing & Engineering 8.3 7.7 93.6%

Education 15.1 14.0 92.8%

Human & Health Sciences 15.3 18.8 122.6%

Applied Sciences 11.8 13.3 112.1%

Art, Design & Architecture 10.6 10.4 98.4%

Again a decline in Computing and Education. Art & Design and Music & Humanities have remained pretty much the same. The other 3 schools have seen an increase in the number of loans per active borrower.

One final set of data — the number of active borrowers per school…

academic school average active borrowers per school % change

2000-2005 2006-2008

Music, Humanities & Media 1,537 1,976 128.5%

Business 2,557 2,963 115.8%

Computing & Engineering 1,650 1,527 92.5%

Education 1,526 1,988 130.3%

Human & Health Sciences 3,587 4,581 127.7%

Applied Sciences 1,267 1,243 98.1%

Art, Design & Architecture 1,621 2,332 143.9%

It looks like there are a couple of things going on here…

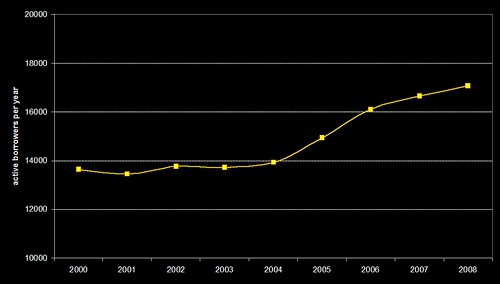

1) In the last 3 years, the number of active borrowers (i.e. users who have borrowed at least one item) has increased. In the period 2000-2004, the total number of active student borrowers was relatively static (around 14,000) and since 2005 it’s been on the increase (with just over 17,000 in 2008).

2) Overall, there’s an increase in the average number of books borrowed per active borrower, primarily driven by the two schools with the highest number of active borrowers (Business and Human & Health). The increases in those two schools more than offsets the decreases seen in a couple of the other schools (Computing and Education).

At a time when some other UK academic libraries have reported a decrease in borrowing, both of the above are good news for our library. I’ll need to go back to the SCONUL stats to check, but I don’t think we’ve seen much of an increase in book stock in the last decade (I suspect it might actually have decreased).

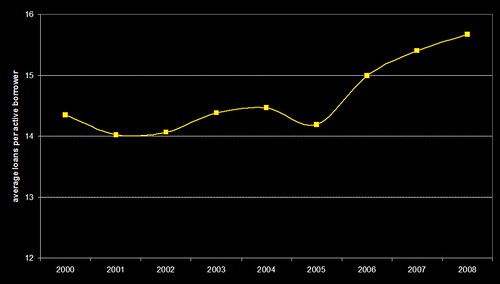

So, can we actually say anything about the impact of serendipity? If we look in more depth at the average number of books borrowed per active borrower per year for all students, we get this…

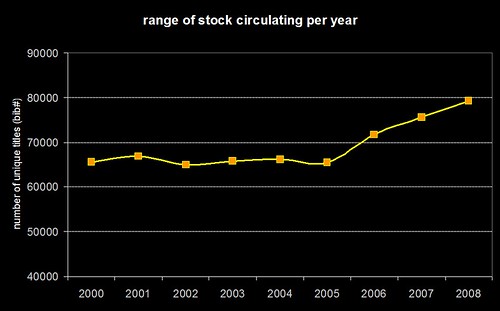

…which closely resembles the original graph from the first post showing the range of unique titles borrowed per year…

…and the number of active borrowers per year also shows a similar trend…

It’s obvious that there’s a driver in there somewhere which has caused the average number of loans per active borrower to increase since 2005. Hand-in-hand there’s been a similar increases in the range of stock that’s being borrowed and the number of active borrowers.

As more people use the library, one would perhaps expect the range of stock being borrowed to increase. However, would you also expect the average number of loans per borrower to increase (bearing in mind that the stock levels have probably not increased and may have actually decreased during that period)?

I’m still not entirely sure I’ve shown that adding serendipity to an OPAC increases the range of stock being borrowed (that’s probably more influenced by the number of active borrowers), but there may well be a link with the average number of books loaned to each borrower.

Now, to change the topic, here’s one final graph that I included in the UKSG presentation — it shows the number of clicks per month on the books in the OPAC’s virtual shelf browser…

…seeing as this was just an experimental feature that added a bit of “book cover eye candy” to the OPAC, I’m amazed how heavily it’s being used. Whilst fixing one of our dedicated catalogue PCs in the library on Friday, I noticed that a student was carrying out a search, then picking a relevant search result, then using the shelf browser to look at all of the nearby books. And to think I’m usually dismissive of the benefits of browsing within OPACs 😀